Research Interests and Projects

|

My work explores the political and institutional dimensions of human-environment relationships, with a focus on rural development and natural resource governance (especially water and forests) in the developing world. My broader theoretical agenda, which I have begun to call a Political Ecology of Citizenship, seeks to understand the political pathways that can bring about more just and sustainable agro-ecological landscapes. Methodologically I employ a mixed-methods approach rooted in intensive qualitative inquiry, complemented with more generalizable knowledge gained from quantitative and geospatial methods. To date, I have conducted a majority of my research in India’s state Himachal Pradesh, with shorter stints of fieldwork in Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, and Telangana.

My newest research project "Institutional Networks and Self-organized Adaptation: Tracing the democratic architectures of climate response" (funded by the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet) explores the political networks through which communities seek support from the state to confront climate risk and change, with sites in India and Nepal. Right: Fields flooded for wet rice cultivation in Kohladi village, where I have been conducting research since 2012. |

Local Democracy and Rural DevelopmentMy dissertation explored the effects of decentralization on local political practice through a study of the implementation of India’s National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA). Drawing on 12 months’ ethnographic fieldwork, I theorized a recursive process of social and institutional change, whereby changing labor economies, shifting forms of social identity, and the restructuring of political institutions led to transformations of local political practice over time. Not only did this enable a wide diversity of aspiring political actors—including many from formerly marginal groups—to actively engage in village politics, it challenged longstanding structures of power and authority in village society, engendering new spaces of popular voice and mobilization to define local development agendas. This research was funded by an NSF Dissertation Improvement Grant (DDRI), a Fulbright-IIE Fellowship, and the University of Illinois Dissertation Completion Fellowship.

In the years following completion of my PhD, I further developed these themes into wider theoretical contributions to the study of local democracy through the papers “Beyond participation and accountability: Theorizing representation in local democracy” published in World Development and "Reshaping the public domain: Decentralization, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), and trajectories of local democracy in rural India" (with Syed S. Ali), also in World Development. Left top: Young women participating in a village meeting Left bottom: Assessing progress on a rainwater collection tank built by the elected village government. |

|

Vulnerability, Adaptation, and Climate Change

My most recent project "Institutional Networks and Self-organized Adaptation: Tracing the democratic architectures of climate response", funded by the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet, €560,000), aims to study how individuals, households, and communities access state support mechanisms to confront climate risk and change, and the political channels that enable (and often preclude) their success. The project is a collaborative effort with Forrest Fleischman, Dil Khatri, and Divya Gupta. Previously, as a postdoc with the Revitalizing Rainfed Agriculture Network (RRA), I explored how combinations of rural institutions and state support systems influence social responses to climate risk and change. Through my involvement with the RRA, I was a part of the design and implementation of a large data collection effort on rainfed livelihoods comprising ~4500 households with sites in five Indian states. Outputs from this research are in progress. Previously, I published a paper (with Ashwini Chhatre) that advances what we have called the ‘profile approach’ to vulnerability analysis, illustrated with an analysis of household assets and livelihoods within 17 villages in the Indian Himalayas. Our approach focuses on household differentiation as a means to tease apart the causes and conditions that shape variegated exposure to risk. This paper, “The Multiple dimensions of vulnerability: Assets and livelihoods in the Indian Himalayas” is published in Environment and Planning A. I have also studied changing production of millets, coarse grain cereals that are both water efficient and drought-resistant. I undertook a short qualitative study on millet cultivation in Ananthapur, Andhra Pradesh which led to the paper, "Can more drought resistant crops promote more climate secure agriculture? Prospects and challenges of millet cultivation in Ananthapur, Andhra Pradesh" published in World Development Perspectives. Several colleagues and I are also studying an area in the lower Kullu Valley of Himachal Pradesh that has seen significant transformations in the rural economy over the past two decades. Apple production was the center of the economy from the 1950s until the 1990s, when it saw a rapid decline due warming temperatures which inhibit pollination. Since then, however, the area has seen extensive diversification into a variety of other crops, while agriculture remains prosperous. Our work explores how access to state institutions, household-level social networks, and natural assets (land and water) have enabled farmers to effectively respond to these challenges. Preliminary findings have been published in the paper "From apple juice to garlic pickle: Climate change adaptation in the Himalayas" in the flagship journal of the Indian School of Business, ISB Insight, and in a blog on Australia India Institute website. |

Top: Farmer in Bihar, India

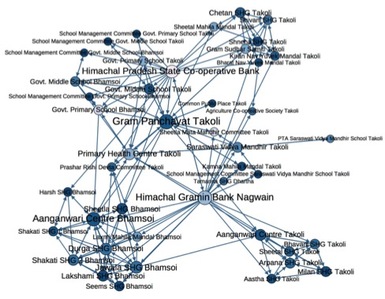

Bottom: A network diagram of interactions between rural institutions, Takoli Panchayat, lower Kullu Valley, Himachal Pradesh |

|

Tree plantations, Carbon Sequestration, and Livelihoods

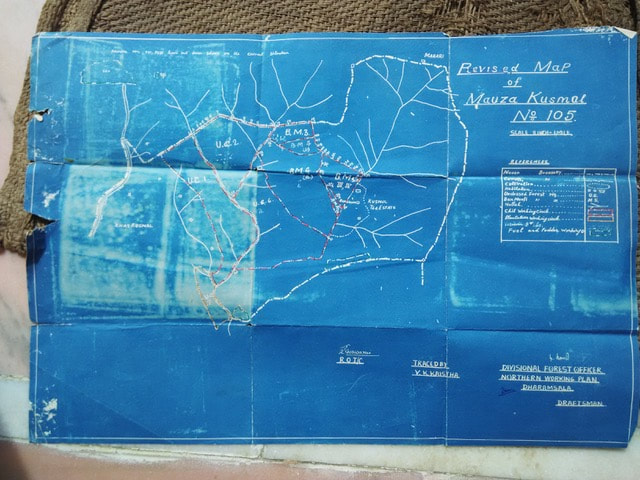

Planting trees has come to be seen as a key strategy for mitigating climate change. Governments, organizations, and private actors around the world have given substantial policy attention to planting trees. But what is this drive to plant more and more trees doing to the livelihoods of people that depend on local natural resources? My colleagues and I—including Fleischman (PI, U. of Minnesota), Pushpendra Rana (U. of Illinois), Vijay Ramprasad (CEDAR), Burak Güneralp (Texas A&M), Anthony Fillipi (Texas A&M), and Eric Coleman (Florida State)—are presently embarking on the project, "Impacts of Afforestation on Sustainable Rural Livelihoods in India”, funded by the United State’s National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to answer this question. Through a combination of remote sensing, quantitative data collection, and qualitative analysis, we are studying how different programs for tree plantations have altered the rural landscape and their effects on livelihoods in the Kangra district of Himachal Pradesh, India—an area that seen very extensive plantations undertaken by the Indian Forest Service in recent decades. Plantations have altered the mixture of benefits that people derive from the landscape, including fuelwood, grazing land, NTFP, and other resource endowments. We are particularly interested in understanding the kinds of interventions and institutional arrangements that enable communities to articulate their interests in plantation processes in order to better align the objective of carbon sequestration with rural livelihood needs. Top left: Landscape with a mosaic of tree plantations, both in foreground and distant hillside Bottom left: An old map from a forest cooperative society in Kangra in an area that has seen extensive plantation over the years. |

Democracy and the State in Common-pool Resource Management

|

In a parallel body of work, I have sought to explore how broader processes of political change, unfolding at multiple sites and scales, influence local practices of natural resource management. Throughout the past eight years working in the middle Himalayas, I have become very interested in the ways that communities have mobilized through state institutions in order to sustain local water resources. My argument is that as the developmental state has come to play a greater role in commons management, self-organized collective action is no longer the primary driver of successful governance; rather, it is increasingly contingent upon the character of democratic citizenship. In the process, the commons has also become a key site of political engagement that influences the very terms of enfranchisement within a broader set of state institutions.

As the first of several outputs from this research, I have written a paper titled "Harnessing the state: social transformation, infrastructural development, and the changing governance of water systems in the Kangra District of Himachal Pradesh, India" published in the Annals of the Association of American Geographers. I now have an article in progress that elaborates the concept of citizenship as a basis to understand how communities, state, and the environment are brought into dialogue through the governance of the commons in the present era. I have discussed this work in a podcast as a part of La Trobe Asia's Asia Rising series. Right: Village men conducting maintenance on an irrigation canal through a project sanctioned by the elected village council and funded with state resources. |

Community Managed Forests and Drivers of Joint Human-environment outcomes

|

Among the most critical challenges of the present era is the need to better align human and environmental objectives. While there is growing evidence of complementarities between livelihood needs and environmental conservation in some contexts, there remains only limited knowledge of the nature of trade-offs between different objectives or the drivers of synergies between them.

Previously, I explored the role of forest management institutions in mediating the relationship between rural livelihoods and biodiversity in common-pool forests. This work was published as a co-authored publication, “Biodiversity conservation and livelihoods in human-dominated landscapes: Forest commons in South Asia” in Biological Conservation. I have also been involved with the Sentinel Landscapes research project, a multi-collaborator effort which is being led by the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). The project explores the interrelations between multiple human and environmental outcomes through analysis of longitudinal data of livelihoods, forest governance, and ecosystem attributes in eight major forested regions around the world. I am presently working on a paper with Arun Agrawal, Ashwini Chhatre, and Anja Gassner that explores the institutional drivers of forest degradation and regeneration in forest commons using a unique global dataset comprising 750 community forests across 23 countries. |

Protected areas and conservation conflictsProtected areas continue to be key sites of political contestation when communities are alienated from resources that they depend upon for their livelihoods. But how do these political engagements, in turn, influence local resource management? Previously, I studied the efforts of resource-dependent women to embark upon a forest management system in the context of a protest movement against a wildlife sanctuary in northern India. Drawing together literature on feminist environmentalism, environmental values, and postcolonial democracy, I argued that what I was observing was an important but under-explored form of conservation politics --- where political mobilization for resource rights can stimulate new kinds of environmental action. This project led to a publication in Geoforum, “Environmental Citizenship, Gender, and the Emergence of a New Conservation Politics”.

Left: Women protesting restrictions on forest use associated with the Dhauladhar Wildlife Sanctuary in Himachal Pradesh, 2009 |